Articles

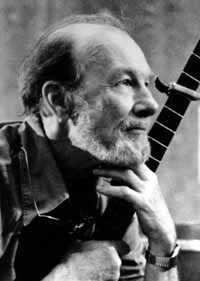

Pete Seeger: "The Most Important Job I Ever Did"

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

Pete Seeger is 86. His shimmering tenor is frail now, his exuberant banjo and ringing guitar less muscular. What remains, however, burning bright and warm as ever, is the force of his personality; his palpable passion for folk music in all its forms and foibles; his deeply cut egalitarianism; and his unshakable belief that humankind, whether it likes it or not, is really one big, global family.

In recent years, thanks in large part to Appleseed Records' wonderful all-star anthologies, "The Songs of Pete Seeger," there has been a major reappraisal of Pete's impact as a songwriter, popularizer of songs, and crucial champion of songwriters from Woody Guthrie and Huddie "Lead Belly" Ledbetter to Bob Dylan, Malvina Reynolds, and Tom Paxton.

But there is a new generation of performers, taking to folk stages in numbers not seen since the commercial folk revival of the 1960s, who never saw him do, in his prime, what many people - including Pete himself - believe was his most important contribution to the culture of music. It was as a concert performer that Pete most profoundly helped shape and reinvent folk music, gently shepherding it from its past as the social music of working people, into the vast and vibrant genre it is today.

"At this age of life," Pete says about his performing, "I'm mainly eager to get the crowd saying, 'I could do that,' and joining in on the songs. Earlier in life, I simply wanted to make the best music I could; and the best music I'd ever heard, the most honest music, was made by people who were not professionals, who just sang for their friends or family or community."

In what he says next, he reveals something of the foundation for his uniquely personal performances. His easygoing, unpretentious stage style is the norm in folk performance today; but in the 1950s, it was seen as radically new, an almost fiercely un-show-bizzy way of treating audiences, singing and speaking with them the same way he would in his living room. And always, he asked them to join him in singing. He did not perform to audiences, but with them.

"These nonprofessionals I admired," he says, "weren't singing to show what a beautiful voice they had, which I didn't like even when it was done in opera, or on Broadway: professionals showing off what a fine voice they had. A fine voice comes off best if its not being shown off, I think, as in any kind of beauty. You know, if you see a beautiful woman who's showing off her looks, it's very different from a beautiful woman who seems almost innocent of her beauty."

Arlo Guthrie has been Pete's frequent performing partner since 1970. He says Pete's personal style works, first and foremost, because it is real. It is Pete being Pete, utterly and authentically.

"I think the force of his personality is probably the major thing that people relate to," he says. "He's a man of principle, and principles are not always convenient. But he's stuck to them, and I think people who know something about him relate to that. And it opens the door immediately for him to be able to craft his magic. All the Seegers I know are like that: principled people, with a very distilled discipline. You know, if Pete was a moonshiner, he'd make really fine stuff."

Pete's grandson, Tao Rodriguez-Seeger, is now in the hot young stringband The Mammals. But he cut his performing teeth performing with his grandfather in the 1990s.

"I think the key to Grandpa's performance style," he says, "is that he genuinely believes - and always has - that through the communal experience of music, people and the world will be made better. It is such a genuine belief - almost a religion with him - that it translates very powerfully to the audience as a performance experience. They get caught up in his fervor, his genuine enthusiasm for togetherness and community through music."

Harold Leventhal began managing Pete's career when he was in the Weavers, the folk quartet that became the most popular vocal group in the country from 1950 until they were blacklisted in the anti-Communist hysteria of the day.

"I've seen Pete perform all over the world," he says, "and it's amazing how audiences respond to him. He was always sort of a teacher, teaching the audience about the music; very relaxed, very direct. I think it works because of the sincerity that comes out of what he's saying. He believes in what he's doing, and he wants you to learn about that. Not necessarily to accept everything, but to be taught a new version of things."

In many ways, Pete has always been the same on stage, presenting himself simply as a lover of folk music; sharing his songs informally, in a way that appears unaffected, informal, and in-the-moment. As a result, many have wondered how spontaneous he really is. Can anybody be that good on stage, and be as casual about it as he seems?

"Oh, give me a break," chuckles Ronnie Gilbert, who sang with Pete in the Weavers. "He knows exactly what he's doing on stage; it's just that what he's doing is being the non-conscious performer. And he's playing it wonderfully. But nobody who gets in front of an audience is unconscious of what they're doing. That's an impossibility, unless you have some serious kind of personality disorder. I think Pete's extraordinarily conscious of what he's doing, and how he's doing it."

Indeed, if Pete's stage style succeeded because he never pretended to be a formal, show-bizzy entertainer, as was the norm when he began his career, it also worked because he never pretended to be a folk, to imitate the nonprofessional, working-class singers he admired so much. Ask him where the line is between folk music and pop music, and he'll say it begins with the words, "Mike check, one-two, mike check."

"In a sense," he says, "every time you take money for performing, you're now a pop singer. So for over 50 years, I've looked at myself as sort of a pop folk singer. Certainly the Weavers were."

Pete was already a pretty seasoned performer when the Weavers debuted at New York's Village Vanguard nightclub in December, 1949. But his background was almost entirely at informal venues, singing alone or with the Almanac Singers at labor rallies, schools, and the informal song-swaps he and his friends dubbed hootenannies.

When asked how influenced he was by Woody Guthrie, his good friend and fellow Almanac singer, Pete says, "Oh, greatly. His use of humor, his kind of deadpan way of doing things: just go ahead and sing the song. But that was pretty natural for me, anyway. You know, I didn't start out singing in nightclubs or concert halls. In 1939, my aunt asked me to sing for her class, got me five dollars for it, and I stopped looking for a job as a journalist. I sang at other schools: three dollars here, two dollars there, but that was a lot of money back then."

So from his first professional appearance, the roles of entertainer and teacher were intertwining, and the venues he played encouraged a casual, conversational style. But would that have to change when the Weaver became nightclub entertainers?

Ronnie Gilbert says, "We all came from the idea of social music, all of us. We all had traditions of social music in our background before we ever came together. The amazing thing is that it worked with an audience that was not specifically a folk audience; and we did it exactly the same way we would have for a hootenanny audience."

Because they were now making decisions as a full-time group, Ronnie says, everything about how to present this music had to be discussed. And in those discussions, much of the template for performing folk songs in the modern musical arena began to take shape.

For example, what to wear? It's worth exploring, not because what they wore ended up being very important, but because it shows how basic the questions were that the Weavers faced in bringing this nonprofessional music form into the ritzy nightclubs and concert halls of the day. And what they decided reveals much about the origins of Pete's performing style.

Should they dress up in formal attire, the way most nightclub entertainers of that day did? Should they dress down, emulating the humble folk from whom they had learned the songs? Ronnie remembers one TV executive who coached them on how to dress for a TV show.

"It was like hayseeds, some stylized version of the country bumpkin," she says with a dry laugh. "Except that in my apron, I would have bagels, and pull them out during our Israeli song. See, that's what we were dealing with, that kind of horrible, ridiculous thinking. We just laughed and dressed the way we usually did."

Harold Leventhal says Pete, the Weavers, and their folk singing compatriots all had a penchant for natural, honest performances.

"Woody was like that, too, and Cisco Houston, and Lead Belly. They were as relaxed as Pete was. The question of how to present it was never a big subject; you just did it. But it was a big departure from the so-called concert stage, and I'll give you an example. When the Weavers got going, and we had a very big record, we were going to do concerts at Town Hall. So I had all the guys get a tuxedo; and my argument was that Paul Robeson always did that. Well, they did get them, but then Pete would come on wearing red socks. So we abandoned that idea right away."

Ronnie says they decided to simply wear street clothes in nightclubs; to dress nicely, but pretty much the same way they would off stage. To make the effect a little more formal, Toshi Seeger took the boys out and bought them matching green corduroy jackets.

"The idea was simply to neutralize clothes as an issue," says Ronnie. "The beauty of it was that we could then just be ourselves, and present the songs the honest way we wanted to."

As Pete became a solo performer, he took that naturalism one step further, showing up in casual slacks or jeans, and a shirt with rolled-up sleeves, just the way he dressed around his Hudson River home. He was not dressing up, not dressing down; he simply appeared the way he would off stage.

That informality, that level of personal authenticity, became profoundly influential for the next generation of folk performers. It just seemed like the way the present these un-gussied-up songs.

As the Weavers found it harder to get work after being blacklisted, Pete went back to playing schools, and slowly entered into what he believes is the most important period of his professional life: traveling the country in the '50s and early '60s, performing at colleges, sowing the seeds of the coming folk revival.

His informal manner, and his desire to blend the roles entertainer and educator, were ideally suited for college concerts. Especially in that era of slick, affected pop stars, his low-key, conversational approach, and his focus on what folk songs showed us about real people's lives, were like catnip to rebellious students looking for a deeper musical experience. In that era of anti-heroes, it can be argued that Pete was the quintessential anti-star.

But there was more to his allure than that. Pete was still working in the shadow of the blacklist. In 1955, he refused to answer questions from the House Un-American Activities Committee, resulting in a conviction for contempt of Congress, which was overturned on appeal in 1962. Attending a Pete Seeger concert in those days was, in and of itself, an act of rebellion.

Arlo Guthrie traces his radical activism to his first Pete Seeger concert, when he was 12 or 13. Of course, he'd known Pete all his life, as one of his father Woody Guthrie's closest friends. But going to his first Seeger concert, he and his pals saw it was being leafleted by members of the right-wing John Birch Society, as Pete's shows often were in those days.

Arlo says, "I asked one of the pamphleteers, 'Is this really true? This guy's a commie, and we're all going to be brainwashed?' And he said, 'Absolutely.' So I said, 'Here, give me those pamphlets; I'll pass them out.' Well, eventually we got all of the pamphlets and, of course, threw them all away. That was my very first political action, and it was due to Pete. Then we went in, and we really wanted to hear what he had to say."

"The poor American Legion and John Birch Society," Pete chuckles, "all those protests did was sell tickets and get me free publicity. The more they protested, the bigger the audiences became; and they didn't really know what to do about it."

Also profoundly influential was Pete's expansive approach to folk music. His shows rambled from cowboy song to sea chantey, African-American spiritual to prison chant, ancient Scottish ballad to Woody Guthrie song, old lullaby to timely original tune.

Even more important than this, according to Arlo, was the fact that Pete did all these songs his own way. He never tried to imitate the vocal styles of the cultures from which he culled his repertoire, never sought to do them just the way they had always been done before. He adapted them freely and creatively, delivering them in his own voice and style.

This honest, personal approach traces back to his first days as a folk singer, and was the way Woody Guthrie, Ronnie Gilbert, Lead Belly, and Cisco Houston all sang folk songs from outside their own cultures. It is difficult to see today how important it was in giving the next generation permission to to not just sing these songs, but to make them their own.

"I wish I could give that a date, because that changed everything," Arlo says. "The day that thought came into their minds, everything changes. Because all of a sudden, there's any number of ways you can do a folk song, and when you extrapolate that, it becomes a matter of finding your own way. You can do a folk song your own way, and it's right; you don't have to do it the way it was done a thousand years before. That's a totally new, modern idea that begins with Pete and his buddies. That's never true in the history of the world before."

"And by doing that," Arlo adds, "you've removed the cultural barrier, the standard by which these songs had been judged. By making the songs his own, Pete allowed somebody like me to take these songs and make them mine."

This went beyond Pete simply using his banjo on a calypso tune, or his own Yankee vocal clip to sing the blues. Pete also put together his own versions of folk songs. For example, he says his oft-covered version of "No Irish Need Apply," depicting the anti-Irish racism of in 19th-century, was actually created from two songs from the 1860s.

"One had better verses," he says, "and the other had a better chorus, so I kind of amalgamated the two tunes, stuck them together, and put it out in the People's Song bulletin as 'No Irish Need Apply.' And it's been sung that way ever since."

"When I sang these songs," he says, "I didn't try to pretend I was a cowboy, or a canal worker, or a black man in prison. And I'd sing these old folk songs, but then sing something I'd made up myself. Now, when I was singing a song, I would sometimes think of the person who would have originally been singing it, and try to sing it as honestly as you could, so that if they heard it, they would say, 'Yup, you've got it. You didn't hit all the notes, but you got the meaning right.'"

During these years, no other folk performer did more to fashion the accepted template of the modern folk singer. Pete's performances helped reinvent what it meant to be a folk singer, and it was his model, more than anyone else's, that was followed by the young folk artists who ignited the '60s folk revival.

"I've said this many times," Pete says, "the most important job I ever did was going to college to college to college in the 1950s. I could really have kicked the bucket in 1960. It helped show all these young people that you could sing these songs and make a living at it. In fact, I was making a good living."

As the revival gathered steam, Pete became its gentle father figure. He floated above most of the generation-gap feuds of the era; embraced equally by rigid purists who scorned much of what the new folk singers were doing; and by the new generation of revival performers.

Much of how he did that is displayed on Columbia Records' two-CD reissue of Pete's entire Carnegie Hall concert from June, 1963. And even more is revealed about the crafty entertainer behind the easygoing folk singer.

He opens the show with soft wisps of banjo, almost as if he is just noodling around. Everyone quiets and focuses. What is he doing? Slowly, his playing takes form and motion, accelerating into a bright-eyed version of "Old Joe Clark," then familiar to nearly all Americans. In a matter of seconds, he has splintered their energy and remolded it into something he can shape and control. It is the move of a brilliant stage tactician.

After a few old folk standards, from ancient mountain ballad to Irish antiwar song, he boldly segues from a silly Woody Guthrie children's song to a similar kiddie-ditty by a new songwriter named Tom Paxton. Pete then devotes the rest of the set to folk's new wave of writers, including Paxton, Malvina Reynolds, and Bob Dylan; winding up with songs emerging from the Southern Civil Rights Movement. Simply through the organic flow of his set, from ancient classic to daring new protest tune, he makes it clear he thinks the new songs are cut from the same cloth as the old ones.

He goes global in the second set, talking about a world trip he plans to take. He romps through songs from places he plans to visit: Brazil, Russia, Japan, Poland, Spain. Revealingly, even here he creates a personal context for singing the songs: he is learning them for his trip.

But there is also a very crafty entertainer at work. In singalongs, for example, he regularly changes not the cadence, but the beats he chooses to emphasize, adding dramatic dynamic changes, and shifts in audience energy, leading them from hushed singing to full-tilt shouting.

He is utterly unafraid to sing the kinds of soggy old standards that most modern folk singers feel they must avoid. There, at Carnegie Hall, he opens his second set with "Skip to My Lou," and it is a pure wonder to hear everybody in that storied hall singing "Flies in the sugar bowl, shoo-shoo-shoo."

Arlo Guthrie remembers a story Pete told him from the world tour Pete took shortly after that Carnegie Hall concert. A Russian writer said, "I listened to your songs, and I didn't know if I could trust you - until you sang songs of your own home on the Hudson River. Then I knew you were somebody I could trust."

Arlo says, "I think Pete walked away with that story kind of burned in his soul. Yeah, it's fine to be this international folk something, but unless he was true to himself, how would somebody else in the world trust that he was not just some propaganda tool?"

"At the same time he was saying all these other things in the '60s, that's what stuck in my mind. He had to do both, and that's how he resolved it. In order for him to be proved truthful singing all these other songs, he would have to also sing songs that came from his own life and background. That's what grounds him, gives him the authority to do all the other songs."

"And you have to remember," Arlo continues, his voice getting excited, "that all this is taking place right after hordes of urban young people are picking up the banjo, the mandolin, and the fiddle for the first time - singing songs for which they have no practical knowledge or relationship: Appalachian songs, cowboy songs, chain-gang songs. So Pete makes that legitimate; he says, go ahead, do it. And more than that, he says you will learn more about those people by singing their songs. And the truth is, that's exactly what happens. And that's also why Pete can get away with writing maple-syrup songs with a Calypso beat."

Throughout his professional life, Pete has been clearly uncomfortable with the adulation of his fans, and the trappings of celebrity. He did not become the quintessential anti-star by accident.

Asked why Pete believes so strongly in getting audiences to sing with him, Tao inexorably connects it to his grandfather's distaste for stardom.

"He wants to get audiences involved because he's tribal at heart, because he believes community, in the truest sense of that word, is where it's at. And singing together is such a wonderful way to share with people. It's so easy. I mean, tribes do it everywhere. We live in a culture that isn't tribal anymore, and I think my Grandpa just yearns for that, that sense of loss of self."

"You know, he never wanted to be famous. He always wanted to be one of the gang. And he gets upset when people treat him special. The few times I've seen him get genuinely angry is when he shows up somewhere, and there's a limo waiting for him, or something like that. He gets furious; he doesn't want to seen as special."

Asked what he's learned about performing from Pete, Tao says, "Confidence, a careful self-confidence; that with good cheer and a smile, nothing can go wrong. He's spontaneous, but he's also observant. I've learned from him how to observe the audience as a whole, to see when something's working and, more important, when it's not."

"He likes to joke that a concert must have a beginning, a muddle, and an end. It has to start, have some tangle, and then you have to wrap the tangle up into some neat little package. But he thinks about it a lot; he always spends lots of time dwelling on what he did the night before. He's always practicing his schtick, listening to what works and what doesn't from the point of view of the listener."

Arlo says, "I learned so much about Pete from performing. He would hate the word, but he's a master at it. I think the first thing I learned was just to assume that everybody is already with you. And that just makes it so much easier; it's not a combative art. Even when you read his testimony at the House Un-American Activities Committee, you can see him fighting to assume that these people who were questioning him were in some way as patriotic as he was - even though he knows they're not."

"One of the things that I think about Pete," Arlo adds, measuring his words carefully, "is that he's a very simple human being. I don't think he was born simple; I think he's just distilled. Some people would call it stubbornness, but I would call it focused. He is the same in his living room as he is in a stadium, and that intimacy is born of his personal belief that we're all in it together. It's not a convenient attitude to have, but it sure works."

Asked what advice he would offer young performers, Pete is quiet for a long time. One can fairly hear that distilling process; all the years, the stages, the troubles and the triumphs; his lifelong passion for the real music made by the real people of the world.

Finally, he says, with a gentle sigh, "I'd say don't make a big thing of it."

Originally appeard in Sing Out! The Folk Music Magazine

In recent years, thanks in large part to Appleseed Records' wonderful all-star anthologies, "The Songs of Pete Seeger," there has been a major reappraisal of Pete's impact as a songwriter, popularizer of songs, and crucial champion of songwriters from Woody Guthrie and Huddie "Lead Belly" Ledbetter to Bob Dylan, Malvina Reynolds, and Tom Paxton.

But there is a new generation of performers, taking to folk stages in numbers not seen since the commercial folk revival of the 1960s, who never saw him do, in his prime, what many people - including Pete himself - believe was his most important contribution to the culture of music. It was as a concert performer that Pete most profoundly helped shape and reinvent folk music, gently shepherding it from its past as the social music of working people, into the vast and vibrant genre it is today.

"At this age of life," Pete says about his performing, "I'm mainly eager to get the crowd saying, 'I could do that,' and joining in on the songs. Earlier in life, I simply wanted to make the best music I could; and the best music I'd ever heard, the most honest music, was made by people who were not professionals, who just sang for their friends or family or community."

In what he says next, he reveals something of the foundation for his uniquely personal performances. His easygoing, unpretentious stage style is the norm in folk performance today; but in the 1950s, it was seen as radically new, an almost fiercely un-show-bizzy way of treating audiences, singing and speaking with them the same way he would in his living room. And always, he asked them to join him in singing. He did not perform to audiences, but with them.

"These nonprofessionals I admired," he says, "weren't singing to show what a beautiful voice they had, which I didn't like even when it was done in opera, or on Broadway: professionals showing off what a fine voice they had. A fine voice comes off best if its not being shown off, I think, as in any kind of beauty. You know, if you see a beautiful woman who's showing off her looks, it's very different from a beautiful woman who seems almost innocent of her beauty."

Arlo Guthrie has been Pete's frequent performing partner since 1970. He says Pete's personal style works, first and foremost, because it is real. It is Pete being Pete, utterly and authentically.

"I think the force of his personality is probably the major thing that people relate to," he says. "He's a man of principle, and principles are not always convenient. But he's stuck to them, and I think people who know something about him relate to that. And it opens the door immediately for him to be able to craft his magic. All the Seegers I know are like that: principled people, with a very distilled discipline. You know, if Pete was a moonshiner, he'd make really fine stuff."

Pete's grandson, Tao Rodriguez-Seeger, is now in the hot young stringband The Mammals. But he cut his performing teeth performing with his grandfather in the 1990s.

"I think the key to Grandpa's performance style," he says, "is that he genuinely believes - and always has - that through the communal experience of music, people and the world will be made better. It is such a genuine belief - almost a religion with him - that it translates very powerfully to the audience as a performance experience. They get caught up in his fervor, his genuine enthusiasm for togetherness and community through music."

Harold Leventhal began managing Pete's career when he was in the Weavers, the folk quartet that became the most popular vocal group in the country from 1950 until they were blacklisted in the anti-Communist hysteria of the day.

"I've seen Pete perform all over the world," he says, "and it's amazing how audiences respond to him. He was always sort of a teacher, teaching the audience about the music; very relaxed, very direct. I think it works because of the sincerity that comes out of what he's saying. He believes in what he's doing, and he wants you to learn about that. Not necessarily to accept everything, but to be taught a new version of things."

In many ways, Pete has always been the same on stage, presenting himself simply as a lover of folk music; sharing his songs informally, in a way that appears unaffected, informal, and in-the-moment. As a result, many have wondered how spontaneous he really is. Can anybody be that good on stage, and be as casual about it as he seems?

"Oh, give me a break," chuckles Ronnie Gilbert, who sang with Pete in the Weavers. "He knows exactly what he's doing on stage; it's just that what he's doing is being the non-conscious performer. And he's playing it wonderfully. But nobody who gets in front of an audience is unconscious of what they're doing. That's an impossibility, unless you have some serious kind of personality disorder. I think Pete's extraordinarily conscious of what he's doing, and how he's doing it."

Indeed, if Pete's stage style succeeded because he never pretended to be a formal, show-bizzy entertainer, as was the norm when he began his career, it also worked because he never pretended to be a folk, to imitate the nonprofessional, working-class singers he admired so much. Ask him where the line is between folk music and pop music, and he'll say it begins with the words, "Mike check, one-two, mike check."

"In a sense," he says, "every time you take money for performing, you're now a pop singer. So for over 50 years, I've looked at myself as sort of a pop folk singer. Certainly the Weavers were."

Pete was already a pretty seasoned performer when the Weavers debuted at New York's Village Vanguard nightclub in December, 1949. But his background was almost entirely at informal venues, singing alone or with the Almanac Singers at labor rallies, schools, and the informal song-swaps he and his friends dubbed hootenannies.

When asked how influenced he was by Woody Guthrie, his good friend and fellow Almanac singer, Pete says, "Oh, greatly. His use of humor, his kind of deadpan way of doing things: just go ahead and sing the song. But that was pretty natural for me, anyway. You know, I didn't start out singing in nightclubs or concert halls. In 1939, my aunt asked me to sing for her class, got me five dollars for it, and I stopped looking for a job as a journalist. I sang at other schools: three dollars here, two dollars there, but that was a lot of money back then."

So from his first professional appearance, the roles of entertainer and teacher were intertwining, and the venues he played encouraged a casual, conversational style. But would that have to change when the Weaver became nightclub entertainers?

Ronnie Gilbert says, "We all came from the idea of social music, all of us. We all had traditions of social music in our background before we ever came together. The amazing thing is that it worked with an audience that was not specifically a folk audience; and we did it exactly the same way we would have for a hootenanny audience."

Because they were now making decisions as a full-time group, Ronnie says, everything about how to present this music had to be discussed. And in those discussions, much of the template for performing folk songs in the modern musical arena began to take shape.

For example, what to wear? It's worth exploring, not because what they wore ended up being very important, but because it shows how basic the questions were that the Weavers faced in bringing this nonprofessional music form into the ritzy nightclubs and concert halls of the day. And what they decided reveals much about the origins of Pete's performing style.

Should they dress up in formal attire, the way most nightclub entertainers of that day did? Should they dress down, emulating the humble folk from whom they had learned the songs? Ronnie remembers one TV executive who coached them on how to dress for a TV show.

"It was like hayseeds, some stylized version of the country bumpkin," she says with a dry laugh. "Except that in my apron, I would have bagels, and pull them out during our Israeli song. See, that's what we were dealing with, that kind of horrible, ridiculous thinking. We just laughed and dressed the way we usually did."

Harold Leventhal says Pete, the Weavers, and their folk singing compatriots all had a penchant for natural, honest performances.

"Woody was like that, too, and Cisco Houston, and Lead Belly. They were as relaxed as Pete was. The question of how to present it was never a big subject; you just did it. But it was a big departure from the so-called concert stage, and I'll give you an example. When the Weavers got going, and we had a very big record, we were going to do concerts at Town Hall. So I had all the guys get a tuxedo; and my argument was that Paul Robeson always did that. Well, they did get them, but then Pete would come on wearing red socks. So we abandoned that idea right away."

Ronnie says they decided to simply wear street clothes in nightclubs; to dress nicely, but pretty much the same way they would off stage. To make the effect a little more formal, Toshi Seeger took the boys out and bought them matching green corduroy jackets.

"The idea was simply to neutralize clothes as an issue," says Ronnie. "The beauty of it was that we could then just be ourselves, and present the songs the honest way we wanted to."

As Pete became a solo performer, he took that naturalism one step further, showing up in casual slacks or jeans, and a shirt with rolled-up sleeves, just the way he dressed around his Hudson River home. He was not dressing up, not dressing down; he simply appeared the way he would off stage.

That informality, that level of personal authenticity, became profoundly influential for the next generation of folk performers. It just seemed like the way the present these un-gussied-up songs.

As the Weavers found it harder to get work after being blacklisted, Pete went back to playing schools, and slowly entered into what he believes is the most important period of his professional life: traveling the country in the '50s and early '60s, performing at colleges, sowing the seeds of the coming folk revival.

His informal manner, and his desire to blend the roles entertainer and educator, were ideally suited for college concerts. Especially in that era of slick, affected pop stars, his low-key, conversational approach, and his focus on what folk songs showed us about real people's lives, were like catnip to rebellious students looking for a deeper musical experience. In that era of anti-heroes, it can be argued that Pete was the quintessential anti-star.

But there was more to his allure than that. Pete was still working in the shadow of the blacklist. In 1955, he refused to answer questions from the House Un-American Activities Committee, resulting in a conviction for contempt of Congress, which was overturned on appeal in 1962. Attending a Pete Seeger concert in those days was, in and of itself, an act of rebellion.

Arlo Guthrie traces his radical activism to his first Pete Seeger concert, when he was 12 or 13. Of course, he'd known Pete all his life, as one of his father Woody Guthrie's closest friends. But going to his first Seeger concert, he and his pals saw it was being leafleted by members of the right-wing John Birch Society, as Pete's shows often were in those days.

Arlo says, "I asked one of the pamphleteers, 'Is this really true? This guy's a commie, and we're all going to be brainwashed?' And he said, 'Absolutely.' So I said, 'Here, give me those pamphlets; I'll pass them out.' Well, eventually we got all of the pamphlets and, of course, threw them all away. That was my very first political action, and it was due to Pete. Then we went in, and we really wanted to hear what he had to say."

"The poor American Legion and John Birch Society," Pete chuckles, "all those protests did was sell tickets and get me free publicity. The more they protested, the bigger the audiences became; and they didn't really know what to do about it."

Also profoundly influential was Pete's expansive approach to folk music. His shows rambled from cowboy song to sea chantey, African-American spiritual to prison chant, ancient Scottish ballad to Woody Guthrie song, old lullaby to timely original tune.

Even more important than this, according to Arlo, was the fact that Pete did all these songs his own way. He never tried to imitate the vocal styles of the cultures from which he culled his repertoire, never sought to do them just the way they had always been done before. He adapted them freely and creatively, delivering them in his own voice and style.

This honest, personal approach traces back to his first days as a folk singer, and was the way Woody Guthrie, Ronnie Gilbert, Lead Belly, and Cisco Houston all sang folk songs from outside their own cultures. It is difficult to see today how important it was in giving the next generation permission to to not just sing these songs, but to make them their own.

"I wish I could give that a date, because that changed everything," Arlo says. "The day that thought came into their minds, everything changes. Because all of a sudden, there's any number of ways you can do a folk song, and when you extrapolate that, it becomes a matter of finding your own way. You can do a folk song your own way, and it's right; you don't have to do it the way it was done a thousand years before. That's a totally new, modern idea that begins with Pete and his buddies. That's never true in the history of the world before."

"And by doing that," Arlo adds, "you've removed the cultural barrier, the standard by which these songs had been judged. By making the songs his own, Pete allowed somebody like me to take these songs and make them mine."

This went beyond Pete simply using his banjo on a calypso tune, or his own Yankee vocal clip to sing the blues. Pete also put together his own versions of folk songs. For example, he says his oft-covered version of "No Irish Need Apply," depicting the anti-Irish racism of in 19th-century, was actually created from two songs from the 1860s.

"One had better verses," he says, "and the other had a better chorus, so I kind of amalgamated the two tunes, stuck them together, and put it out in the People's Song bulletin as 'No Irish Need Apply.' And it's been sung that way ever since."

"When I sang these songs," he says, "I didn't try to pretend I was a cowboy, or a canal worker, or a black man in prison. And I'd sing these old folk songs, but then sing something I'd made up myself. Now, when I was singing a song, I would sometimes think of the person who would have originally been singing it, and try to sing it as honestly as you could, so that if they heard it, they would say, 'Yup, you've got it. You didn't hit all the notes, but you got the meaning right.'"

During these years, no other folk performer did more to fashion the accepted template of the modern folk singer. Pete's performances helped reinvent what it meant to be a folk singer, and it was his model, more than anyone else's, that was followed by the young folk artists who ignited the '60s folk revival.

"I've said this many times," Pete says, "the most important job I ever did was going to college to college to college in the 1950s. I could really have kicked the bucket in 1960. It helped show all these young people that you could sing these songs and make a living at it. In fact, I was making a good living."

As the revival gathered steam, Pete became its gentle father figure. He floated above most of the generation-gap feuds of the era; embraced equally by rigid purists who scorned much of what the new folk singers were doing; and by the new generation of revival performers.

Much of how he did that is displayed on Columbia Records' two-CD reissue of Pete's entire Carnegie Hall concert from June, 1963. And even more is revealed about the crafty entertainer behind the easygoing folk singer.

He opens the show with soft wisps of banjo, almost as if he is just noodling around. Everyone quiets and focuses. What is he doing? Slowly, his playing takes form and motion, accelerating into a bright-eyed version of "Old Joe Clark," then familiar to nearly all Americans. In a matter of seconds, he has splintered their energy and remolded it into something he can shape and control. It is the move of a brilliant stage tactician.

After a few old folk standards, from ancient mountain ballad to Irish antiwar song, he boldly segues from a silly Woody Guthrie children's song to a similar kiddie-ditty by a new songwriter named Tom Paxton. Pete then devotes the rest of the set to folk's new wave of writers, including Paxton, Malvina Reynolds, and Bob Dylan; winding up with songs emerging from the Southern Civil Rights Movement. Simply through the organic flow of his set, from ancient classic to daring new protest tune, he makes it clear he thinks the new songs are cut from the same cloth as the old ones.

He goes global in the second set, talking about a world trip he plans to take. He romps through songs from places he plans to visit: Brazil, Russia, Japan, Poland, Spain. Revealingly, even here he creates a personal context for singing the songs: he is learning them for his trip.

But there is also a very crafty entertainer at work. In singalongs, for example, he regularly changes not the cadence, but the beats he chooses to emphasize, adding dramatic dynamic changes, and shifts in audience energy, leading them from hushed singing to full-tilt shouting.

He is utterly unafraid to sing the kinds of soggy old standards that most modern folk singers feel they must avoid. There, at Carnegie Hall, he opens his second set with "Skip to My Lou," and it is a pure wonder to hear everybody in that storied hall singing "Flies in the sugar bowl, shoo-shoo-shoo."

Arlo Guthrie remembers a story Pete told him from the world tour Pete took shortly after that Carnegie Hall concert. A Russian writer said, "I listened to your songs, and I didn't know if I could trust you - until you sang songs of your own home on the Hudson River. Then I knew you were somebody I could trust."

Arlo says, "I think Pete walked away with that story kind of burned in his soul. Yeah, it's fine to be this international folk something, but unless he was true to himself, how would somebody else in the world trust that he was not just some propaganda tool?"

"At the same time he was saying all these other things in the '60s, that's what stuck in my mind. He had to do both, and that's how he resolved it. In order for him to be proved truthful singing all these other songs, he would have to also sing songs that came from his own life and background. That's what grounds him, gives him the authority to do all the other songs."

"And you have to remember," Arlo continues, his voice getting excited, "that all this is taking place right after hordes of urban young people are picking up the banjo, the mandolin, and the fiddle for the first time - singing songs for which they have no practical knowledge or relationship: Appalachian songs, cowboy songs, chain-gang songs. So Pete makes that legitimate; he says, go ahead, do it. And more than that, he says you will learn more about those people by singing their songs. And the truth is, that's exactly what happens. And that's also why Pete can get away with writing maple-syrup songs with a Calypso beat."

Throughout his professional life, Pete has been clearly uncomfortable with the adulation of his fans, and the trappings of celebrity. He did not become the quintessential anti-star by accident.

Asked why Pete believes so strongly in getting audiences to sing with him, Tao inexorably connects it to his grandfather's distaste for stardom.

"He wants to get audiences involved because he's tribal at heart, because he believes community, in the truest sense of that word, is where it's at. And singing together is such a wonderful way to share with people. It's so easy. I mean, tribes do it everywhere. We live in a culture that isn't tribal anymore, and I think my Grandpa just yearns for that, that sense of loss of self."

"You know, he never wanted to be famous. He always wanted to be one of the gang. And he gets upset when people treat him special. The few times I've seen him get genuinely angry is when he shows up somewhere, and there's a limo waiting for him, or something like that. He gets furious; he doesn't want to seen as special."

Asked what he's learned about performing from Pete, Tao says, "Confidence, a careful self-confidence; that with good cheer and a smile, nothing can go wrong. He's spontaneous, but he's also observant. I've learned from him how to observe the audience as a whole, to see when something's working and, more important, when it's not."

"He likes to joke that a concert must have a beginning, a muddle, and an end. It has to start, have some tangle, and then you have to wrap the tangle up into some neat little package. But he thinks about it a lot; he always spends lots of time dwelling on what he did the night before. He's always practicing his schtick, listening to what works and what doesn't from the point of view of the listener."

Arlo says, "I learned so much about Pete from performing. He would hate the word, but he's a master at it. I think the first thing I learned was just to assume that everybody is already with you. And that just makes it so much easier; it's not a combative art. Even when you read his testimony at the House Un-American Activities Committee, you can see him fighting to assume that these people who were questioning him were in some way as patriotic as he was - even though he knows they're not."

"One of the things that I think about Pete," Arlo adds, measuring his words carefully, "is that he's a very simple human being. I don't think he was born simple; I think he's just distilled. Some people would call it stubbornness, but I would call it focused. He is the same in his living room as he is in a stadium, and that intimacy is born of his personal belief that we're all in it together. It's not a convenient attitude to have, but it sure works."

Asked what advice he would offer young performers, Pete is quiet for a long time. One can fairly hear that distilling process; all the years, the stages, the troubles and the triumphs; his lifelong passion for the real music made by the real people of the world.

Finally, he says, with a gentle sigh, "I'd say don't make a big thing of it."

Originally appeard in Sing Out! The Folk Music Magazine